Your First Electric Car Could Be a Vintage Ford Bronco

- by GQ

- Oct 02, 2024

- 0 Comments

- 0 Likes Flag 0 Of 5

Kindred Motorworks’ flagship product: A vintage Bronco rebuilt with modern comforts.

Save Save

This story was featured in The Must Read, a newsletter in which our editors recommend one can’t-miss story every weekday. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

“Old cars are beautiful, but they’re not functional,” Rob Howard told me one day this spring. “People don’t really elect to admit it, that they’re a pain in the ass. And you tend to find reasons not to drive them.” Howard isn’t immune to their charms, to be sure: He has a small collection of cars he tinkers with, including a 1957 Chevy Bel Air wagon and an ’88 Toyota Land Cruiser. But to commute to and from work, he admitted, he drives a Rivian R1T electric truck. It’s just easier.

We were speaking in his office, not far from San Francisco, surrounded by beautiful old cars in the process of being made functional. Howard is the founder and CEO of a small but growing company called Kindred Motorworks, which is in the business of something called restomodding: upgrading classic cars to be more reliable, more street-friendly, with new engines and modern safety features—and, in Kindred’s case, adding the option of rechargeable, battery-powered electric motors. The trend is not new, exactly, but it got juiced over the past couple years as electrification technology became available to hobbyists and body shops. It’s now possible to turn an old gas-guzzler into an electric car, provided you don’t shock yourself to death. The appeal is obvious: All kinds of people, but especially people with a surplus of both cash and taste, want to drive a rare, classic automobile around town. At the same time, a lot of the same people are increasingly open to going electric. And so a small group of companies has emerged to turn everything from an old Porsche 911 to a vintage VW bus into something you can plug in overnight.

Heaven for car nerds: The Kindred workshop, with a vintage Bronco in mid- restoration.

Restomodding isn’t quite as heady as the purist’s version of car restoration—what you see at car shows known as concours d’elegance, where the aim is to present classic automobiles as if they’ve just rolled off the factory floor, in flawless condition with original parts. But giving an old car modern power steering and air-conditioning, and a Bluetooth stereo system, never mind an electric power train, isn’t exactly affordable. Florida’s FJ Company had me lusting this year over one of their own refurbished Land Cruisers (sticker price: $266,800). In the United Kingdom, Everrati will electrify an old Porsche, starting at around £240,000 (that’s more than $300,000). Zelectric in San Diego, which has a two-year waiting list, will retrofit your father’s 1969 Karmann Ghia with disc brakes, LED lights, and Tesla batteries (plus reaching 120 horsepower). Kindred, meanwhile, has focused on the humble Ford Bronco.

So far, customers for electrified restomods are about who you’d think: Robert Downey Jr. made a whole TV show, Downey’s Dream Cars, about his efforts to green-ify his vintage car collection. Julia Roberts, a Kindred rep told me, has pre-ordered one of its electrified VW microbuses. And, yes, one of Kindred’s electrified Broncos starts at more than 200 grand. “This is a luxury good,” Howard said. “We don’t apologize for that because there’s a huge amount of craftsmanship involved in this thing. A very unique vehicle.”

When I visited, the company was producing four Broncos a month, though they were on track, Howard said, to soon make 10 a month. In any case, it was already sold out of everything it would be able to produce through 2025. But Howard really got my attention when he said he planned to cap electric Bronco production at 100 vehicles a year—not for scarcity, he explained, but because Broncos weren’t the only car of interest.

Just outside his office sat gleaming vehicles that had been overhauled with new engines and modern parts: several Broncos, but also an electrified 1953 Chevy 3100 truck (the kind that look designed for drag racing), and an electrified 1958 Volkswagen microbus (the kind that look designed for hotboxing). The plan, Howard explained, was to soon have three lines of production running at the same time: one each for electric and internal combustion Broncos (they’d received as many preorders for the EVs as for the gas-powered), plus one for electric VW buses. And if that worked, and demand stayed steady, selling 100 versions of each model each year, then he’d expand and take on other vintage models and do the same thing: refurbish, modernize, and electrify, all at a steadily growing clip.

Kindred HQ is basically a gigantic toy shop for car nerds. Vehicles litter the factory floor and parking lots in every state of existence: total ruin, gradual repair, and glittering perfection. I spent some time there this spring because I wondered how a scrappy young company, quietly applying Silicon Valley know-how to vintage restoration, will basically beat Ford to market with a fully electrified version of one of its most beloved vehicles. But I left curious about something much bigger than that: whether Kindred might be able to bring a little bit of sex appeal back to American highways.

Kindred has sold out its planned run of vehicles through 2025.

When I was growing up, my father’s daily driver was a BMW 3 Series, followed by a Saab 9000. Over the years he also bought and worked on a 1964 dark-blue Ford Thunderbird, a convertible 1972 Buick Gran Sport in cardinal red, and a moss green 1970 Mercedes-Benz 280 SL. His first project was a 1947 Ford Fordor, dark green, that he inherited from my grandfather, who bought it new and then painted orange stripes down the sides so he’d have an easier time finding it in parking lots.

Zebra marks notwithstanding, I remember thinking myself pretty sophisticated, driving that car as a teenager, gritting my teeth while toggling the steering--column-mounted gearshift to pick up a high school girlfriend for a date. That car, though, like every prize in my dad’s collection, wasn’t on the road very much. Mostly, it sat in the garage. It broke down. It needed expensive repairs. Together, his cars were financial sinkholes that eventually led my father to give up the hobby entirely and start leasing Volvos. Still, they looked cool as hell.

Modern car ownership means making a version of the same compromise my dad did. Drive anywhere in the States and you’ll be hypnotized by banality: Practically every new car looks the same, and the look is boring, pedestrian, smooth-brained. Ignore the badges, take off your glasses, and see if you can tell the difference from 20 paces between a Porsche Cayenne and an Audi Q5—or a Nissan Rogue, or a Kia Sorento. Even the model names sound both aspirational and bland: the Telluride, the Sierra, the Sequoia. The commercials advertising these vehicles suggest we all dream of fleeing our cul-de-sacs for the wilderness, but the reality is more like piloting toaster ovens to football practice.

Admittedly, in the still evolving EV world, things aren’t quite as dreary. I live in Los Angeles, where the streets are menaced lately by so many Tesla Cybertrucks, often murdered out in matte black. Insecure macho or not, at least they look unique. (When you picture a Cybertruck, do you ever imagine a woman driving one? If so, is she happy?) But the rest of Elon Musk’s lineup inclines toward mediocrity, looks-wise, and the same for all the Lucids and Rivians. And, anyway, Tesla is said to be in its slump era. Rivian has endured waves of layoffs this year. Ford reported losing $1.3 billion on the sale of 10,000 electric vehicles in the first three months of 2024. Howard, the Kindred CEO, wants to provide us with the best of both worlds: the voluptuousness of yesterday combined with the eco requirements and on-road performance we’ll need tomorrow, if not today.

Director of research and development Seth Friesen.

Technical manager Skyler Brand.

Howard didn’t get into the business of rejuvenating old cars from the typical route (learning on the job in a garage). His story is more tech founder than Top Gear: A former environmental engineer from Pennsylvania, Howard founded and sold two companies in California (a manufacturing-operations-and--supply-chain firm and a software company that developed a platform for same-day delivery) before starting Kindred. In 2017 he sold the software company to Target, but stayed on to learn the retail business’s ins and outs. At the same time, he spent nights working on his vintage cars, mostly because he liked spinning wrenches and working with his hands.

Over time, Howard realized that he had accumulated an odd portfolio of skills: supply-chain know-how, expertise in software, and Target-honed retail whizbang, not to mention a few core colleagues who’d followed him from company to company. An idea for a new venture, one that drew on his affection for old cars, began to coalesce in his mind.

Restomodding, historically, was a bespoke business: lots of time and attention pointed at specific solutions for specific cars. What if he tried doing what a conversion shop could not? Rather than pursue the builds as one-off projects, he’d attempt to modernize and sell a lot of them—as luxury products, to be sure, but with price tags below half a million bucks. If he were to try such a thing, he reasoned, it would make sense to do it in the backyard he knew well—in his case, the Bay Area tech world, with familiar Silicon Valley workplace benefits like equity for employees and free lunch. The thinking was: Maybe here’s a side door into the auto world that no one had tried.

Founder and CEO Rob Howard.

Kindred’s headquarters are located in what is basically a massive barn atop an odd piece of Bay Area history: Mare Island (technically a peninsula), a landmass about three and a half miles long and one mile wide that juts into San Pablo Bay. It used to host a naval shipyard, until it was closed by the government in the 1990s. Today, the area has a ghostly feel—beautiful old federal buildings and Victorian houses sitting empty, with faded signage and flaking paint. But then other structures are freshly painted, in some cases retooled by new businesses like Kindred, which acquired its space in March 2023. “A year and a half ago, there were no walls or anything, just dirt floor,” one of the company’s executives told me, showing me around what now was a modern car factory.

Indeed, the space felt like an auto plant in miniature, or an Italian carmaker from the 1960s. Separate departments occupied bays laid out along an open floor plan: fabrication, upholstery, spray booths for paint. There weren’t any giant robots. Everything was being done by hand; its head of upholstery showed me how the seat coverings were stitched. Employees stripped old bodies down to parts, welded frames, did axle things to axle things. (Look, I can change my own oil, but that’s the extent of my auto-mechanic skills.) Still, they allowed me to help attach a dashboard to a Bronco in progress, to get a sense of what it would be like to order one for myself: Kindred customers often visit the factory and spend hours participating in its builds.

The company is populated by true believers. Before coming to Kindred, Jesse Thomas, one of the technicians, spent six years working at Tesla’s factory in Fremont, California. Getting to the Kindred offices required a round-trip commute of three to four hours, he told me, but he didn’t mind it; the job felt more meaningful. He loved how the cars were handmade, bespoke, practically artisanal. Also because while there was a sense of urgency on the floor, it wasn’t an emergency. “It’s just so much more fulfilling,” Thomas said.

A rusty Bronco in Kindred’s boneyard, where cars are stripped before being retooled.

Of course, the company hasn’t yet reached the kind of scale that manufactures emergencies. But Kindred seems unlikely to face one problem that EV manufacturers like Tesla and Rivian confronted initially, and have struggled with at times: the need to innovate every single part of their designs. Those companies have given themselves the task of literally creating vehicles no one has ever seen before. On top of that, they’ve also taken on the nuts and bolts of modern auto manufacturing: strength calculations, crash-testing, the works. “We’re the exact opposite,” Howard said. “We’re about craftsmanship. We’re driven by labor. Our goal is to use existing parts and integrate them together, and that dramatically changes our research and development.”

Howard showed me what he meant on one of the tablets that were ubiquitous around the factory. It contained an electronic instruction manual, constantly being updated with photos and tips, describing every single step Kindred developed to tear down and build up each car perfectly. (In the case of some of the Broncos, instructions run to 5,000 steps.) It meant, Howard explained, that highly skilled workers, though not necessarily master technicians, could grab a tablet, step in, and build a car more or less solo—and not electrocute themselves. In a way, it sounded to me like the sort of thing the White House has been trying to implement—in fantasyland or not—as a step toward actually making stuff in this country again: jobs that don’t require a college degree to fabricate incredible things. And perhaps Kindred’s size and the modest scale of its ambitions—hundreds of cars a year, not thousands—gave it a better shot at success. “Legacy and EV start-ups invest billions to get one new model to market,” Howard wrote me later in an email. A return to craftsmanship “unlocks our ability to rapidly improve.”

Kindred delivered its first refurbished Bronco in November 2023. Customer number three, Dan Clark, an entrepreneur in Philadelphia, received his in January 2024, and had since put 2,721 miles on it. He said the purchase was motivated primarily by nostalgia; his high school ride was a 1996 Bronco. But when his Kindred showed up in the driveway, he told me, fond feelings gave way to engineering admiration. “The product blew me away,” he said. “That’s hard to do these days, when you look at all the cars out there.”

So, the question was: How did the Kindreds drive? I began with a restomodded 1958 Volkswagen microbus (starting at $225,000). Painted a surfy seafoam green, it had been updated with improved rear suspension, modern tires, and an electric motor. This was the same bus that had made Julia Roberts smile, and I discovered why: driving around, the ride was cushy, zippy, just plain fun. And I got similar grins from people watching the groovy bus silently slide by. “I call it a smile machine,” Howard said. “And it’ll do 70 on the freeway, no problem.”

Next, the Broncos, which I expected to be different animals. My memory of riding in an old Bronco was that it was pretty frightening at high speed. I hopped in Kindred’s gas-fueled model first, based on a frame from 1972. Everything about it was gorgeous and new—couture seeming, almost, from rich upholstery to gauges that looked handcrafted. And on the road, the new engine, a 460-horsepower Ford third--generation Coyote 5.0 V8, roared when I gunned it—and that sound definitely took me back. At speed, however, the truck felt surprisingly rooted, even when cornering, despite the short wheelbase and tall stature.

“I call it a smile machine,” Kindred’s CEO says of his electrified VW bus. “And it’ll do 70 on the freeway, no problem.”

But restomodding an old Bronco with a new internal-combustion engine, however fun to drive, isn’t the future we require—electrification is. And if the White House remains dead set on stoking a trade war with China, where cool new EV models seem to roll out every week, then I wanted to get a taste of some homegrown innovation, even if it’s out of my budget. The team put me in its prototype EV model, built on a 1968 shell. And right away, the ride was typical of electrics: quiet, easy, effortless power. It rode just like the gas Bronco, except…nicer. I reached a stoplight before a straightaway. I wanted to let it rip, but there was a cop right behind me. Well, I thought: Fuck it.

The light went green and in no time—a couple of seconds?—I hit 70 miles an hour, grinning like a Labrador. The cop, I realized moments later, was actually private security, but it felt good to zip away nonetheless. Kindred may not take over the auto industry anytime soon—that’s not its ambition. But the future it’s pointing toward might just give us a chance to have our cake and drive it too.

An updated Bronco inside Kindred’s Bay Area factory.

Rosecrans Baldwin is a frequent contributor to GQ and the best-selling author of ‘Everything Now: Lessons From the City-State of Los Angeles.’

A version of this story originally appeared in the October 2024 issue of GQ with the title “Make Your First Electric Car an Old Ford Bronco”

Related Stories for GQ

Please first to comment

Related Post

Stay Connected

Tweets by elonmuskTo get the latest tweets please make sure you are logged in on X on this browser.

Sponsored

Popular Post

Middle-Aged Dentist Bought a Tesla Cybertruck, Now He Gets All the Attention He Wanted

32 ViewsNov 23 ,2024

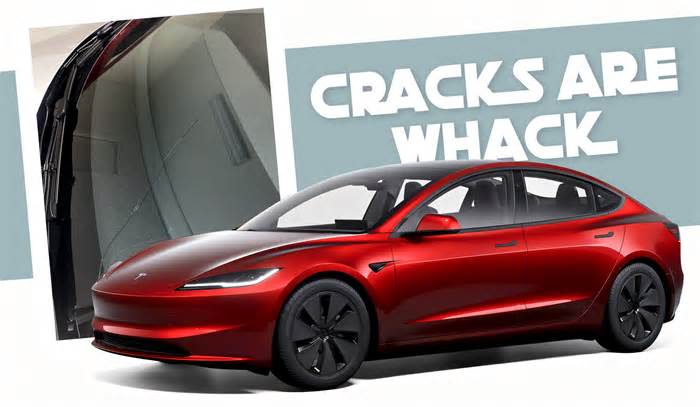

tesla Model 3 Owner Nearly Stung With $1,700 Bill For Windshield Crack After Delivery

32 ViewsDec 28 ,2024

Energy

Energy