How Elon Musk’s Sci-Fi Hyperloop Failed

- by Washingtonian

- Feb 12, 2026

- 0 Comments

- 0 Likes Flag 0 Of 5

February 12, 2026

“We have no idea what we’re doing,” declared Elon Musk, standing beside a yawning “test trench” in Southern California in 2017. A crowd of engineering students and tech reporters hooted and hollered, grinned and nodded, charmed that a man so brilliant could be so modest.

It was a simpler time. The billionaire mogul had not yet built an electric truck liable to fall apart while in motion; released a chatbot known to praise Adolf Hitler; or seemingly succumbed to the same sort of wealth-induced psychosis that had led previous generations of tycoons to embark on fatal hot-air-balloon expeditions and store their urine in jars. He had not yet promised to end climate change with a constellation of sun-blocking satellites, or end poverty with mass-produced humanoid robots, or end the Decline of Western Civilization by dismantling the federal agency responsible for saving untold numbers of children around the world.

Before all that, Musk was considered a genius—and he was going to end the scourge of traffic by digging a bunch of tunnels.

Through a venture called the Boring Company, Musk pledged to reduce the per-mile cost of boring a tunnel from $1 billion to $10 million. Then he would fill his tunnels with large pods capable of traveling 700 miles per hour, three times faster than the world’s fastest train. This system, called hyperloop, would shorten multi-week voyages to 12 hours. It would reshape human history, as did the steamship and automobile. It would first connect Washington to Baltimore, then expand to Philadelphia and New York City. It would be built in two short years, without one cent of taxpayer money.

This grand vision, as you may have already surmised, was never realized. Though permits were issued and politicians insisted the hyperloop was imminent, the effort died in 2021. Then it was never mentioned again. In early 2025, shortly after Musk and his Department of Government Efficiency ordered the nation’s spies to share, via email, five things they had accomplished at work the previous week, I set out to understand how the hyperloop project—his original attempt to bring private-sector innovation to the public sector—went sideways.

In the beginning, I expected to uncover a scam gone awry, a suspicion that deepened after I contacted dozens of government officials and employees of the Boring Company. Not one person who had previously advocated for the hyperloop was willing to talk, even off the record. But after I spoke with a handful of well-placed sources, it became clear there was no conspiracy, no evidence of fraud.

The truth was far simpler, far dumber, and far more prescient: Musk and his lieutenants truly had no idea what they were doing. Among most insiders, this was always apparent. But our leaders, for any number of reasons—including political opportunism and an earnest if foolhardy desire to make commuting less miserable—chose to support the effort anyway. This is the story of how fantasy becomes policy, time and again.

he proclamation was delivered in fewer than 160 characters. “Just received verbal govt approval for The Boring Company to build an underground NY-Phil-Balt-DC Hyperloop. NY-DC in 29 minutes,” Musk wrote in July 2017. He did not specify which government, sending public-affairs offices into a frenzy.

“Who gave him permission to do that?” wrote a baffled spokesperson for the Maryland Department of Transportation.

“This is the first we’re hearing of this,” added LaToya Foster, a spokesperson for DC mayor Muriel Bowser.

Not one state or city government was privy to these discussions. The US Department of Transportation was also taken by surprise, referring all press inquiries to the White House, where Donald Trump was six months into his first term and otherwise preoccupied with exerting handshake dominance over French president Emmanuel Macron; hiring and ten days later firing Anthony Scaramucci as his communications director; and nearly regaling thousands of boys at the National Scout Jamboree with lurid tales about a rich friend’s yacht parties.

A day after the announcement, Musk walked back his claim but added no further clarity. “Still a lot of work before formal, written approval, but this opens door for state & city discussions,” he posted.

Months later, something vaguely resembling a plan was released. Phase one of the hyperloop would run from DC’s NoMa to Baltimore’s Camden Yards and feature two parallel, 35.3-mile tunnels running primarily beneath the Baltimore-Washington Parkway. The basic premise behind hyperloop, first put forth by Musk in 2013, was to shoot pods full of people and cargo through vacuum-sealed tubes. The pods would float atop a thin cushion of air while electric motors accelerated them toward the speed of sound. Unlike existing commuter infrastructure, this system would be fast, low-fare, and privately funded. Because it was mostly underground, there would be little to no need to seize private property through eminent domain or shut down high-traffic roads for months on end. There would be no reason to worry about anything at all, because the world’s biggest brains had everything under control. A dozen firms raced to field the first workable prototype, collectively raising more than a billion dollars from venture capitalists.

Many local officials were cautiously optimistic, but the challenges were obvious. Tunneling is inherently difficult: The ground is full of stuff, like gas lines and boulders, and we have no idea where most of that stuff is located until we start digging. Though Musk pledged to reduce the cost by two orders of magnitude, he offered no road map for mitigating the technical realities that make boring so expensive. The other hurdle, unique to the region, was the regulatory ringer: The proposed route would need sign-offs from the District of Columbia, the city of Baltimore, the state of Maryland, the Federal High-way Administration, the National Park Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers.

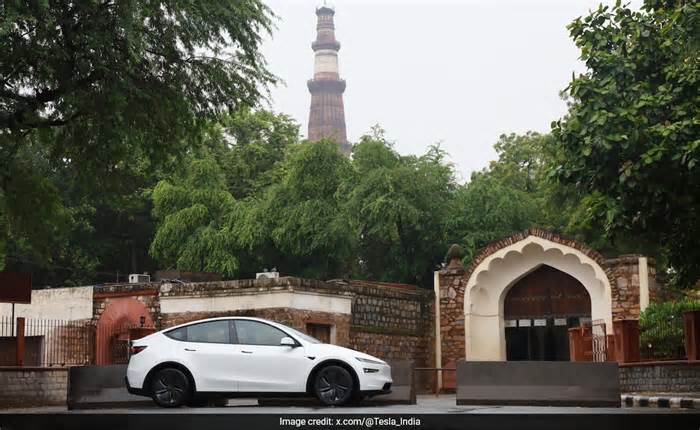

In Musk’s grand vision, the hyperlop would end the scourge of traffic–and perhaps reshape human history, as did the steamship and automobile.

Davis had won eternal glory at SpaceX, Musk’s aerospace company, for dramatically reducing the cost of rocket-control systems. (In 2007, according to the New York Times, he allegedly removed too many essential components from the Falcon 1, causing the rocket to plunge into the Pacific Ocean.) Eventually, he was tasked with laying off 80 percent of the workforce at Twitter following Musk’s takeover in 2022—and later with overseeing the carnage wrought by DOGE.

His hyperloop collaborators, however, remember Davis as “some guy with the yogurt shop” and “a total weirdo.” A longtime District resident, he was the proud owner of Mr. Yogato, a quirky frozen-yogurt establishment in Dupont Circle; Thomas Foolery, a now-shuttered board-game bar that specialized in Smirnoff Ice; and several parking lots in Navy Yard, where he was known to hold walking meetings while placing tickets on the windshields of delinquent vehicles.

Throughout the summer of 2017, the White House Office of American Innovation, led by Trump son-in-law and real-estate heir Jared Kushner, arranged meetings between Davis and local leaders. Mayor Bowser’s transit team was jazzed to learn more about the technology. But their first meeting with the Boring Company—which did not respond to requests for comment—was a disaster. “These were not serious people,” said one participant.

“It was all conceptual. There was no actual thing,” added a former senior executive in the District Department of Transportation. Attendees asked basic questions. In the hyperloop’s vacuum-sealed environment, even a small rupture in the concrete shell could lead to explosive decompression, killing everyone inside. So could the tunnels withstand earthquakes? There was also the matter of topography: The region is famously swampy, which means the soil is damp and prone to collapse. Underground projects have historically required specialized pumps, real-time structural reinforcement, and well-thought-out plans to avoid destroying deep-pile building foundations throughout the city. Had that been factored into the cost projections, which were vastly below the price of recent mega projects?

The Boring Company hadn’t considered these issues. “It was all so obvious, but they didn’t see it,” said one transit official. “They came in thinking this is cool and it has Elon Musk attached, so it’s inevitable.”

District officials pumped the brakes—but their counterparts in Maryland plowed ahead. Governor Larry Hogan and secretary of transportation Pete Rahn had been branded enemies of public transit, and they needed a win. The governor had already unilaterally canceled the light-rail project known as the Baltimore Red Line, a wildly controversial decision that prompted a federal investigation. Then he eliminated more funding for rapid-bus and rail expansion. A privately funded spectacle could help boost Hogan’s favorables without requiring any new spending. The duo went all in on hyperloop. (Hogan, Rahn, two former gubernatorial chiefs of staff, and six state transportation executives did not respond to requests for comment.)

Typically, it takes years to move from announcing an infrastructure project to ordering a big ceremonial shovel. On September 13, 2017, only five weeks after Musk’s initial post, a political strategist representing the Boring Company emailed John Falcicchio, then Mayor Bowser’s chief of staff. Maryland was ready to chat about the “upcoming groundbreaking.”

Falcicchio—who did not respond to an interview request—was flustered. “When you say upcoming,” he wrote back, “how soon do you mean?”

teve Davis, the man of many vocations, took charge of planning the groundbreaking. The event had to leave an impression. It needed to embarrass the skeptics—and demonstrate, beyond any reasonable doubt, that hyperloop was imminent.

“Proposed plan,” he wrote. “On MD land, we put up a big, screened fence w/ TBC sign.”

This seemingly was good enough for Hogan’s administration. A big screened fence went up near Fort Meade, and the governor set aside 20 minutes in his calendar. When the big day arrived, four men—Hogan, Rahn, Davis, and Anne Arundel County Executive Steve Schuh—posed for photos in front of a chain-link fence, which was wrapped in vinyl sheeting translucent enough to reveal an empty field: no heavy machinery, no porta-potties, no broken ground. They did not answer questions, because no reporters had been invited.

Toward the end of the gathering, an aide approached Hogan, filming a video. “Gov, what do you think about the Boring Company’s hyperloop?” she asked.

“I think . . . it’s coming to Maryland,” he mumbled, adjusting his sunglasses. “It’s going to go from Baltimore to Washington. So, uh, get ready.”

That was, more or less, the extent of the state’s knowledge. Still, the Hogan administration embraced the idea, inflating the hype bubble. “This thing is real. It’s exciting to see,” said Rahn in one interview. “The word ‘transformational’ may be overused, but this is a technology that leapfrogs any technology that is out there today, and it’s going to be here.”

The state’s leaders went to great lengths to please the Boring Company. They held weekly calls on hyperloop, and the invite list included nearly 50 officials from across government. When reporters sought records related to the project under the Public Information Act, Boring Company executives were permitted to approve documents before they were released. The state also circumvented the typically slow-moving permit process using a crafty workaround: issuing a simple utility permit, arguing that building a concrete shell underground wasn’t all that different from installing new pipes or electrical conduits. Meanwhile, DC officials made pilgrimages to the Boring Company’s California headquarters, home to the 500-ton tunneling apparatus that Musk had bought secondhand from another company. Musk named the machine Godot—the titular character from a play about a man who is expected to deliver salvation but never shows up, leaving believers disgraced and suicidal.

The hyperloop’s issues were “all so obvious, but they didn’t see it. They came in thinking this is cool and it has Elon Musk attached, so it’s inevitable.”

Kushner’s team focused on bypassing the regulatory process, including the comprehensive assessment required under the National Environmental Policy Act. These reviews, which can take several years and run to more than a thousand pages, are meant to evaluate—and offer ways to mitigate—unintended consequences. Would this project introduce new sources of pollution, erosion hazards, or flooding risks? Could the planned route inadvertently hollow out communities or reduce the productivity of important agricultural land? Could this initiative somehow make traffic worse?

The White House had no interest in forethought. According to a former senior transportation official, the Trump administration set a one-month deadline, alarming civil servants. “Those environmental folks at [the Federal Highway Administration] are legit,” said the official. “I ordinarily had to beg, borrow, and steal to get them to expedite a process from three years to two years.”

The District Department of Transportation, still concerned, slow-walked the approval process, issuing a vague and largely meaningless permit for site preparation at 53 New York Avenue, Northeast, a vacant lot in NoMa. A former official described this as an act of placation. “This was 100 percent a federal initiative,” they explained. “This was never a priority for us. The federal government approached us, so we engaged, because they fund a lot of our transit projects.” (Mayor Bowser, as well as three senior advisers from this period, did not respond to requests for comment. Her office redacted almost every document released to Washingtonian under the Freedom of Information Act, citing deliberative privilege.)

By 2018, the hyperloop effort in Maryland was losing steam. In January, the state attorney general’s office alleged that the utility permit was improper, owing to the fact that a train is not a utility—permits are reserved for infrastructure such as fiber-optic internet and cable television, electricity and gas, sewage and water. Then, in March, six local members of Congress sent a long list of oversight questions to state officials, urging them to take their time during the planning phase. Hogan dismissed their concerns. “Some of MD’s representatives in DC aren’t content with spreading their bureaucratic malaise in our nation’s capital—they seem determined to bring it to our state’s capital, as well,” he said in a now-deleted post. “Nothing is going to stand in the way of our progress.”

n reality, many things stood in the way, including but not limited to the laws of thermodynamics. The hyperloop industry was flailing. Companies were burning through cash much faster than they could raise it, and every field test offered a new reason to despair.

Hyperloop Alpha, the original design that Team Musk put forth, was a flop. They’d proposed using a high-pressure air cushion to levitate the passenger pods, but when third-party engineers put that concept to the test, they discovered two big problems. Compressing the air required an outrageous amount of energy, making the system less fuel-efficient than air travel. The resulting air gap was also too thin for real-world scenarios. Even a millimeter-scale misalignment in the track, caused by shifting earth or routine wear and tear, could cause fatal accidents. Companies instead began experimenting with magnetic levitation, similar to bullet trains in East Asia—but in braking tests, they struggled to safely operate vehicles faster than 240 miles per hour, a third of the speed originally promised.

The Boring Company pivoted again. In March 2018, Musk unveiled his new vision: In a rendered video, a 16-person autonomous vehicle resembling an oversize bedside humidifier zipped along an underground road. This was just a bus, with a dedicated lane.

Soon after, the Boring Company gathered reporters in California for a highly anticipated demo. But there was no high-speed, self-driving bus. Instead, a Tesla Model X SUV carried passengers through a short tunnel, sometimes approaching 50 miles an hour and ricocheting so violently that one journalist fell ill. Musk’s new-new vision was just a car, moving slower than it would aboveground. “I thought it was epic,” he told reporters. “It was an epiphany.”

Four months after that shambolic demonstration, the US and Maryland transportation departments finally released their draft assessment. As expected, it took much longer than one month, and the contents affirmed what everyone with eyes had already concluded: There would be no hyperloop. In fact, the term had been stripped from the document and replaced with “the loop.” Instead of a sci-fi subway, a fleet of self-driving Teslas would move passengers between two existing train stations, under an existing highway, moving at max speeds comparable to that of Amtrak’s Acela train, which travels about 150 miles an hour. The future had arrived, and it looked a lot like the present.

During the public-comment period, the Maryland Department of Transportation received nearly 500 complaints, comments, and questions from other government agencies, many noting fatal flaws. Safety was the most concerning issue. The Loop would be the longest road tunnel in the world, and it would be packed with electric vehicles known to spontaneously combust inside suburban garages. The structure needed a rock-solid evacuation plan—but proposed escape routes were spaced up to two miles apart, connected to the surface by ladders as tall as a high-rise apartment building. “You’d die in the tunnel,” said one person close to the planning process.

Ridership was another issue. The new, less ambitious system could move only 1,000 people per direction per day. You could cram more passengers onto a single eight-car Metro train. The assessment acknowledged that the system “would not change travel patterns in the region,” and if that was true, the Boring Company would never come close to covering its costs. “It had so many holes in it. It was embarrassing,” said a former senior official with the District Department of Transportation.

A year passed, and the Boring Company, once in near-constant contact, grew distant.

Another year passed, and Maryland was still waiting for Godot.

By April 2021, communication had ceased. MDOT began referring all questions to the Boring Company. Likewise, the US Department of Transportation claimed it hadn’t received “any indication from the company that they are interested in moving forward with the project.” The company stopped answering the phone as soon as its proposal faced any serious scrutiny, then scrubbed all the evidence from its website. The same thing happened in Chicago, Los Angeles, San Bernardino, San Jose, and San Antonio.

here is only one city where the Boring Company has delivered a final product, one governing body willing to double down on this wager. In 2019, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, a powerful planning board largely funded by hotel-room taxes, set out to build a state-of-the-art people mover beneath the city’s convention center. The Boring Company was awarded the contract, despite having no record of past performance. Local authorities have allowed the company to skirt numerous regulatory requirements, and the tunnels have seemingly been run like something out of Mad Max. Since construction began, according to government inspection reports and investigations by Fortune and ProPublica, numerous workers and firefighters have lost their skin to calf-deep pools of caustic sludge. Fifty-pound rocks have fallen from overhead conveyor belts. Among laborers, drinking water can be scarce, extreme heat can be punishing, and body parts have been crushed inside heavy machinery. In total, the Boring Company has failed to conduct more than 700 routine inspections. (The Boring Company did not respond to requests for comment, nor did it provide comment to Fortune or ProPublica. It has disputed the workplace-safety violations with state authorities.)

The city of Las Vegas bet big on this idea, spending at least $77 million. In return, it received a one-mile tunnel beneath the convention facility, which now branches off to several neighboring casinos. Within the tunnel, a fleet of 62 cars, driven by independent contractors, carries passengers at speeds approaching 40 miles per hour. When passengers take too long to exit their vehicle or unload their luggage, there is traffic. Occasionally, cars run into each other, requiring the other cars to reverse out of the tunnel. Teenagers love to trespass and skateboard through the space. Absentminded drivers make errant turns off Las Vegas Boulevard and get lost underground.

If passengers ask about any of these issues, drivers will dutifully change the subject, as instructed by their handbook, instead explaining that Musk is a “great leader” and this boondoggle is “awesome.”

he hyperloop hype cycle has run its course. The last arguably serious research-and-development company, Hyperloop One, shut down in 2023. The Boring Company hasn’t carried out a test in at least six years—its demo tunnel outside of SpaceX was long ago turned into employee parking. The proposed terminal in NoMa was sold to a developer and presumably will be turned into luxury apartments. The web domain for the DC-to-Baltimore route has been commandeered by foreign SEO marketers, who converted the site into an unintelligible guide to online gambling.

The official narrative is that this failure cost taxpayers nothing, because it was a privately funded lark. But that’s not entirely correct. Though the government never spent a dollar on digging, staffers spent years trying to make an unworkable idea work: holding meetings, carrying out studies, and expending time and effort that otherwise could have been devoted to something actually useful.

The web domain for the DC-to-Baltimore hyperloop project is now an unintelligible guide to online gambling.

In a sensible world, a fiasco of this sort would conclude in the manner of a sitcom. The oafish dad who tried to install a backyard swimming pool—and instead opened a sinkhole that swallowed the neighbor’s convertible—would feel remorse. He’d host an apology barbecue, where the mayor would gently remind him that he’ll never be allowed to operate heavy machinery again. Everybody would learn from the experience.

But we do not live in that world. If we did, the President would not have picked Musk to lead his government-reinvention effort. The hyperloop hypeman wouldn’t have deployed a squad of baby-faced engineers and Silicon Valley types, led by none other than Steve Davis, to fire 300,000 government workers and still somehow fail to save any money—nor would he have quit after a few months, admitting the whole thing was a mistake. The shareholders of Tesla wouldn’t have paid their absentee CEO a record-setting $56 billion while the company was flagging. Venture capitalists wouldn’t continue to pump cash into ventures like the Boring Company, which somehow lives on today.

Over the past decade, the Boring Company has dug only a few miles of operational tunnel. It has never cracked $23 million in reported annual revenue. Its tunneling machines still move about ten times slower than a common snail. Yet, for reasons inexplicable to anyone who doesn’t worship at the altar of high finance, it is valued at $7 billion. Every year, the company’s leaders issue a new guarantee: The solution is within their grasp if only they can throw a little bit more of someone else’s money at the problem. Every time, a fresh group of naifs—most recently, the state of Tennessee, which last year contracted the company to construct a Vegas-style Tesla tunnel between downtown Nashville and the city’s airport—chooses to believe their shiny promises.

We believe them because we want to believe them. We want to believe that we ourselves are not the problem, that there aren’t too many cars on the road. We want to believe that we are masters of this universe, unconstrained by physics. We want to believe that progress—in all its forms—is born from audacity alone and does not also require collective action, patience, and occasional sacrifice. We want to believe that big things can be easy instead of hard and that belief itself can make them so.

And so we gamble. We pull the slot-machine lever once more, just one last time, confident that it will be different from all the other times. Surely it will be different this time. It has to be different this time.

This article appears in the February 2026 issue of Washingtonian.

“We have no idea what we’re doing,” declared Elon Musk, standing beside a yawning “test trench” in Southern California in 2017. A crowd of engineering students and tech reporters hooted and hollered, grinned and nodded, charmed that a man so brilliant could be so modest.

It was a simpler time. The billionaire mogul had not yet built an electric truck liable to fall apart while in motion; released a chatbot known to praise Adolf Hitler; or seemingly succumbed to the same sort of wealth-induced psychosis that had led previous generations of tycoons to embark on fatal hot-air-balloon expeditions and store their urine in jars. He had not yet promised to end climate change with a constellation of sun-blocking satellites, or end poverty with mass-produced humanoid robots, or end the Decline of Western Civilization by dismantling the federal agency responsible for saving untold numbers of children around the world.

Before all that, Musk was considered a genius—and he was going to end the scourge of traffic by digging a bunch of tunnels.

Through a venture called the Boring Company, Musk pledged to reduce the per-mile cost of boring a tunnel from $1 billion to $10 million. Then he would fill his tunnels with large pods capable of traveling 700 miles per hour, three times faster than the world’s fastest train. This system, called hyperloop, would shorten multi-week voyages to 12 hours. It would reshape human history, as did the steamship and automobile. It would first connect Washington to Baltimore, then expand to Philadelphia and New York City. It would be built in two short years, without one cent of taxpayer money.

This grand vision, as you may have already surmised, was never realized. Though permits were issued and politicians insisted the hyperloop was imminent, the effort died in 2021. Then it was never mentioned again. In early 2025, shortly after Musk and his Department of Government Efficiency ordered the nation’s spies to share, via email, five things they had accomplished at work the previous week, I set out to understand how the hyperloop project—his original attempt to bring private-sector innovation to the public sector—went sideways.

In the beginning, I expected to uncover a scam gone awry, a suspicion that deepened after I contacted dozens of government officials and employees of the Boring Company. Not one person who had previously advocated for the hyperloop was willing to talk, even off the record. But after I spoke with a handful of well-placed sources, it became clear there was no conspiracy, no evidence of fraud.

The truth was far simpler, far dumber, and far more prescient: Musk and his lieutenants truly had no idea what they were doing. Among most insiders, this was always apparent. But our leaders, for any number of reasons—including political opportunism and an earnest if foolhardy desire to make commuting less miserable—chose to support the effort anyway. This is the story of how fantasy becomes policy, time and again.

he proclamation was delivered in fewer than 160 characters. “Just received verbal govt approval for The Boring Company to build an underground NY-Phil-Balt-DC Hyperloop. NY-DC in 29 minutes,” Musk wrote in July 2017. He did not specify which government, sending public-affairs offices into a frenzy.

“Who gave him permission to do that?” wrote a baffled spokesperson for the Maryland Department of Transportation.

“This is the first we’re hearing of this,” added LaToya Foster, a spokesperson for DC mayor Muriel Bowser.

Not one state or city government was privy to these discussions. The US Department of Transportation was also taken by surprise, referring all press inquiries to the White House, where Donald Trump was six months into his first term and otherwise preoccupied with exerting handshake dominance over French president Emmanuel Macron; hiring and ten days later firing Anthony Scaramucci as his communications director; and nearly regaling thousands of boys at the National Scout Jamboree with lurid tales about a rich friend’s yacht parties.

A day after the announcement, Musk walked back his claim but added no further clarity. “Still a lot of work before formal, written approval, but this opens door for state & city discussions,” he posted.

Months later, something vaguely resembling a plan was released. Phase one of the hyperloop would run from DC’s NoMa to Baltimore’s Camden Yards and feature two parallel, 35.3-mile tunnels running primarily beneath the Baltimore-Washington Parkway. The basic premise behind hyperloop, first put forth by Musk in 2013, was to shoot pods full of people and cargo through vacuum-sealed tubes. The pods would float atop a thin cushion of air while electric motors accelerated them toward the speed of sound. Unlike existing commuter infrastructure, this system would be fast, low-fare, and privately funded. Because it was mostly underground, there would be little to no need to seize private property through eminent domain or shut down high-traffic roads for months on end. There would be no reason to worry about anything at all, because the world’s biggest brains had everything under control. A dozen firms raced to field the first workable prototype, collectively raising more than a billion dollars from venture capitalists.

Many local officials were cautiously optimistic, but the challenges were obvious. Tunneling is inherently difficult: The ground is full of stuff, like gas lines and boulders, and we have no idea where most of that stuff is located until we start digging. Though Musk pledged to reduce the cost by two orders of magnitude, he offered no road map for mitigating the technical realities that make boring so expensive. The other hurdle, unique to the region, was the regulatory ringer: The proposed route would need sign-offs from the District of Columbia, the city of Baltimore, the state of Maryland, the Federal High-way Administration, the National Park Service, and the Army Corps of Engineers.

Musk needed a skilled diplomat as his chief executive officer. Instead, he tapped Steve Davis, a rocket scientist, libertarian economist, and notorious penny-pincher whom Musk once compared to chemotherapy: brutally effective but toxic in large doses.

Davis had won eternal glory at SpaceX, Musk’s aerospace company, for dramatically reducing the cost of rocket-control systems. (In 2007, according to the New York Times, he allegedly removed too many essential components from the Falcon 1, causing the rocket to plunge into the Pacific Ocean.) Eventually, he was tasked with laying off 80 percent of the workforce at Twitter following Musk’s takeover in 2022—and later with overseeing the carnage wrought by DOGE.

His hyperloop collaborators, however, remember Davis as “some guy with the yogurt shop” and “a total weirdo.” A longtime District resident, he was the proud owner of Mr. Yogato, a quirky frozen-yogurt establishment in Dupont Circle; Thomas Foolery, a now-shuttered board-game bar that specialized in Smirnoff Ice; and several parking lots in Navy Yard, where he was known to hold walking meetings while placing tickets on the windshields of delinquent vehicles.

Throughout the summer of 2017, the White House Office of American Innovation, led by Trump son-in-law and real-estate heir Jared Kushner, arranged meetings between Davis and local leaders. Mayor Bowser’s transit team was jazzed to learn more about the technology. But their first meeting with the Boring Company—which did not respond to requests for comment—was a disaster. “These were not serious people,” said one participant.

“It was all conceptual. There was no actual thing,” added a former senior executive in the District Department of Transportation. Attendees asked basic questions. In the hyperloop’s vacuum-sealed environment, even a small rupture in the concrete shell could lead to explosive decompression, killing everyone inside. So could the tunnels withstand earthquakes? There was also the matter of topography: The region is famously swampy, which means the soil is damp and prone to collapse. Underground projects have historically required specialized pumps, real-time structural reinforcement, and well-thought-out plans to avoid destroying deep-pile building foundations throughout the city. Had that been factored into the cost projections, which were vastly below the price of recent mega projects?

The Boring Company hadn’t considered these issues. “It was all so obvious, but they didn’t see it,” said one transit official. “They came in thinking this is cool and it has Elon Musk attached, so it’s inevitable.”

District officials pumped the brakes—but their counterparts in Maryland plowed ahead. Governor Larry Hogan and secretary of transportation Pete Rahn had been branded enemies of public transit, and they needed a win. The governor had already unilaterally canceled the light-rail project known as the Baltimore Red Line, a wildly controversial decision that prompted a federal investigation. Then he eliminated more funding for rapid-bus and rail expansion. A privately funded spectacle could help boost Hogan’s favorables without requiring any new spending. The duo went all in on hyperloop. (Hogan, Rahn, two former gubernatorial chiefs of staff, and six state transportation executives did not respond to requests for comment.)

Typically, it takes years to move from announcing an infrastructure project to ordering a big ceremonial shovel. On September 13, 2017, only five weeks after Musk’s initial post, a political strategist representing the Boring Company emailed John Falcicchio, then Mayor Bowser’s chief of staff. Maryland was ready to chat about the “upcoming groundbreaking.”

Falcicchio—who did not respond to an interview request—was flustered. “When you say upcoming,” he wrote back, “how soon do you mean?”

teve Davis, the man of many vocations, took charge of planning the groundbreaking. The event had to leave an impression. It needed to embarrass the skeptics—and demonstrate, beyond any reasonable doubt, that hyperloop was imminent.

“Proposed plan,” he wrote. “On MD land, we put up a big, screened fence w/ TBC sign.”

This seemingly was good enough for Hogan’s administration. A big screened fence went up near Fort Meade, and the governor set aside 20 minutes in his calendar. When the big day arrived, four men—Hogan, Rahn, Davis, and Anne Arundel County Executive Steve Schuh—posed for photos in front of a chain-link fence, which was wrapped in vinyl sheeting translucent enough to reveal an empty field: no heavy machinery, no porta-potties, no broken ground. They did not answer questions, because no reporters had been invited.

Toward the end of the gathering, an aide approached Hogan, filming a video. “Gov, what do you think about the Boring Company’s hyperloop?” she asked.

“I think . . . it’s coming to Maryland,” he mumbled, adjusting his sunglasses. “It’s going to go from Baltimore to Washington. So, uh, get ready.”

That was, more or less, the extent of the state’s knowledge. Still, the Hogan administration embraced the idea, inflating the hype bubble. “This thing is real. It’s exciting to see,” said Rahn in one interview. “The word ‘transformational’ may be overused, but this is a technology that leapfrogs any technology that is out there today, and it’s going to be here.”

The state’s leaders went to great lengths to please the Boring Company. They held weekly calls on hyperloop, and the invite list included nearly 50 officials from across government. When reporters sought records related to the project under the Public Information Act, Boring Company executives were permitted to approve documents before they were released. The state also circumvented the typically slow-moving permit process using a crafty workaround: issuing a simple utility permit, arguing that building a concrete shell underground wasn’t all that different from installing new pipes or electrical conduits. Meanwhile, DC officials made pilgrimages to the Boring Company’s California headquarters, home to the 500-ton tunneling apparatus that Musk had bought secondhand from another company. Musk named the machine Godot—the titular character from a play about a man who is expected to deliver salvation but never shows up, leaving believers disgraced and suicidal.

Kushner’s team focused on bypassing the regulatory process, including the comprehensive assessment required under the National Environmental Policy Act. These reviews, which can take several years and run to more than a thousand pages, are meant to evaluate—and offer ways to mitigate—unintended consequences. Would this project introduce new sources of pollution, erosion hazards, or flooding risks? Could the planned route inadvertently hollow out communities or reduce the productivity of important agricultural land? Could this initiative somehow make traffic worse?

The White House had no interest in forethought. According to a former senior transportation official, the Trump administration set a one-month deadline, alarming civil servants. “Those environmental folks at [the Federal Highway Administration] are legit,” said the official. “I ordinarily had to beg, borrow, and steal to get them to expedite a process from three years to two years.”

The District Department of Transportation, still concerned, slow-walked the approval process, issuing a vague and largely meaningless permit for site preparation at 53 New York Avenue, Northeast, a vacant lot in NoMa. A former official described this as an act of placation. “This was 100 percent a federal initiative,” they explained. “This was never a priority for us. The federal government approached us, so we engaged, because they fund a lot of our transit projects.” (Mayor Bowser, as well as three senior advisers from this period, did not respond to requests for comment. Her office redacted almost every document released to Washingtonian under the Freedom of Information Act, citing deliberative privilege.)

By 2018, the hyperloop effort in Maryland was losing steam. In January, the state attorney general’s office alleged that the utility permit was improper, owing to the fact that a train is not a utility—permits are reserved for infrastructure such as fiber-optic internet and cable television, electricity and gas, sewage and water. Then, in March, six local members of Congress sent a long list of oversight questions to state officials, urging them to take their time during the planning phase. Hogan dismissed their concerns. “Some of MD’s representatives in DC aren’t content with spreading their bureaucratic malaise in our nation’s capital—they seem determined to bring it to our state’s capital, as well,” he said in a now-deleted post. “Nothing is going to stand in the way of our progress.”

n reality, many things stood in the way, including but not limited to the laws of thermodynamics. The hyperloop industry was flailing. Companies were burning through cash much faster than they could raise it, and every field test offered a new reason to despair.

Hyperloop Alpha, the original design that Team Musk put forth, was a flop. They’d proposed using a high-pressure air cushion to levitate the passenger pods, but when third-party engineers put that concept to the test, they discovered two big problems. Compressing the air required an outrageous amount of energy, making the system less fuel-efficient than air travel. The resulting air gap was also too thin for real-world scenarios. Even a millimeter-scale misalignment in the track, caused by shifting earth or routine wear and tear, could cause fatal accidents. Companies instead began experimenting with magnetic levitation, similar to bullet trains in East Asia—but in braking tests, they struggled to safely operate vehicles faster than 240 miles per hour, a third of the speed originally promised.

The Boring Company pivoted again. In March 2018, Musk unveiled his new vision: In a rendered video, a 16-person autonomous vehicle resembling an oversize bedside humidifier zipped along an underground road. This was just a bus, with a dedicated lane.

Soon after, the Boring Company gathered reporters in California for a highly anticipated demo. But there was no high-speed, self-driving bus. Instead, a Tesla Model X SUV carried passengers through a short tunnel, sometimes approaching 50 miles an hour and ricocheting so violently that one journalist fell ill. Musk’s new-new vision was just a car, moving slower than it would aboveground. “I thought it was epic,” he told reporters. “It was an epiphany.”

Four months after that shambolic demonstration, the US and Maryland transportation departments finally released their draft assessment. As expected, it took much longer than one month, and the contents affirmed what everyone with eyes had already concluded: There would be no hyperloop. In fact, the term had been stripped from the document and replaced with “the loop.” Instead of a sci-fi subway, a fleet of self-driving Teslas would move passengers between two existing train stations, under an existing highway, moving at max speeds comparable to that of Amtrak’s Acela train, which travels about 150 miles an hour. The future had arrived, and it looked a lot like the present.

During the public-comment period, the Maryland Department of Transportation received nearly 500 complaints, comments, and questions from other government agencies, many noting fatal flaws. Safety was the most concerning issue. The Loop would be the longest road tunnel in the world, and it would be packed with electric vehicles known to spontaneously combust inside suburban garages. The structure needed a rock-solid evacuation plan—but proposed escape routes were spaced up to two miles apart, connected to the surface by ladders as tall as a high-rise apartment building. “You’d die in the tunnel,” said one person close to the planning process.

Ridership was another issue. The new, less ambitious system could move only 1,000 people per direction per day. You could cram more passengers onto a single eight-car Metro train. The assessment acknowledged that the system “would not change travel patterns in the region,” and if that was true, the Boring Company would never come close to covering its costs. “It had so many holes in it. It was embarrassing,” said a former senior official with the District Department of Transportation.

A year passed, and the Boring Company, once in near-constant contact, grew distant.

Another year passed, and Maryland was still waiting for Godot.

By April 2021, communication had ceased. MDOT began referring all questions to the Boring Company. Likewise, the US Department of Transportation claimed it hadn’t received “any indication from the company that they are interested in moving forward with the project.” The company stopped answering the phone as soon as its proposal faced any serious scrutiny, then scrubbed all the evidence from its website. The same thing happened in Chicago, Los Angeles, San Bernardino, San Jose, and San Antonio.

here is only one city where the Boring Company has delivered a final product, one governing body willing to double down on this wager. In 2019, the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority, a powerful planning board largely funded by hotel-room taxes, set out to build a state-of-the-art people mover beneath the city’s convention center. The Boring Company was awarded the contract, despite having no record of past performance. Local authorities have allowed the company to skirt numerous regulatory requirements, and the tunnels have seemingly been run like something out of Mad Max. Since construction began, according to government inspection reports and investigations by Fortune and ProPublica, numerous workers and firefighters have lost their skin to calf-deep pools of caustic sludge. Fifty-pound rocks have fallen from overhead conveyor belts. Among laborers, drinking water can be scarce, extreme heat can be punishing, and body parts have been crushed inside heavy machinery. In total, the Boring Company has failed to conduct more than 700 routine inspections. (The Boring Company did not respond to requests for comment, nor did it provide comment to Fortune or ProPublica. It has disputed the workplace-safety violations with state authorities.)

The city of Las Vegas bet big on this idea, spending at least $77 million. In return, it received a one-mile tunnel beneath the convention facility, which now branches off to several neighboring casinos. Within the tunnel, a fleet of 62 cars, driven by independent contractors, carries passengers at speeds approaching 40 miles per hour. When passengers take too long to exit their vehicle or unload their luggage, there is traffic. Occasionally, cars run into each other, requiring the other cars to reverse out of the tunnel. Teenagers love to trespass and skateboard through the space. Absentminded drivers make errant turns off Las Vegas Boulevard and get lost underground.

If passengers ask about any of these issues, drivers will dutifully change the subject, as instructed by their handbook, instead explaining that Musk is a “great leader” and this boondoggle is “awesome.”

he hyperloop hype cycle has run its course. The last arguably serious research-and-development company, Hyperloop One, shut down in 2023. The Boring Company hasn’t carried out a test in at least six years—its demo tunnel outside of SpaceX was long ago turned into employee parking. The proposed terminal in NoMa was sold to a developer and presumably will be turned into luxury apartments. The web domain for the DC-to-Baltimore route has been commandeered by foreign SEO marketers, who converted the site into an unintelligible guide to online gambling.

The official narrative is that this failure cost taxpayers nothing, because it was a privately funded lark. But that’s not entirely correct. Though the government never spent a dollar on digging, staffers spent years trying to make an unworkable idea work: holding meetings, carrying out studies, and expending time and effort that otherwise could have been devoted to something actually useful.

In a sensible world, a fiasco of this sort would conclude in the manner of a sitcom. The oafish dad who tried to install a backyard swimming pool—and instead opened a sinkhole that swallowed the neighbor’s convertible—would feel remorse. He’d host an apology barbecue, where the mayor would gently remind him that he’ll never be allowed to operate heavy machinery again. Everybody would learn from the experience.

But we do not live in that world. If we did, the President would not have picked Musk to lead his government-reinvention effort. The hyperloop hypeman wouldn’t have deployed a squad of baby-faced engineers and Silicon Valley types, led by none other than Steve Davis, to fire 300,000 government workers and still somehow fail to save any money—nor would he have quit after a few months, admitting the whole thing was a mistake. The shareholders of Tesla wouldn’t have paid their absentee CEO a record-setting $56 billion while the company was flagging. Venture capitalists wouldn’t continue to pump cash into ventures like the Boring Company, which somehow lives on today.

Over the past decade, the Boring Company has dug only a few miles of operational tunnel. It has never cracked $23 million in reported annual revenue. Its tunneling machines still move about ten times slower than a common snail. Yet, for reasons inexplicable to anyone who doesn’t worship at the altar of high finance, it is valued at $7 billion. Every year, the company’s leaders issue a new guarantee: The solution is within their grasp if only they can throw a little bit more of someone else’s money at the problem. Every time, a fresh group of naifs—most recently, the state of Tennessee, which last year contracted the company to construct a Vegas-style Tesla tunnel between downtown Nashville and the city’s airport—chooses to believe their shiny promises.

We believe them because we want to believe them. We want to believe that we ourselves are not the problem, that there aren’t too many cars on the road. We want to believe that we are masters of this universe, unconstrained by physics. We want to believe that progress—in all its forms—is born from audacity alone and does not also require collective action, patience, and occasional sacrifice. We want to believe that big things can be easy instead of hard and that belief itself can make them so.

And so we gamble. We pull the slot-machine lever once more, just one last time, confident that it will be different from all the other times. Surely it will be different this time. It has to be different this time.

This article appears in the February 2026 issue of Washingtonian.

Join the conversation!

Please first to comment

Related Post

Stay Connected

Tweets by elonmuskTo get the latest tweets please make sure you are logged in on X on this browser.

Energy

Energy